Beating the stock market is not that big of a deal. What’s really impressive — and what you should be looking for when using performance scoreboards to choose a mutual fund — is one that has beaten the market over several successive periods.

To understand why, it’s helpful to imagine a world in which stocks follow a random walk. In such a world, about half of a group of monkeys picking stocks at random would beat the market in any given period. That’s why beating the market is not, in and of itself, that impressive.

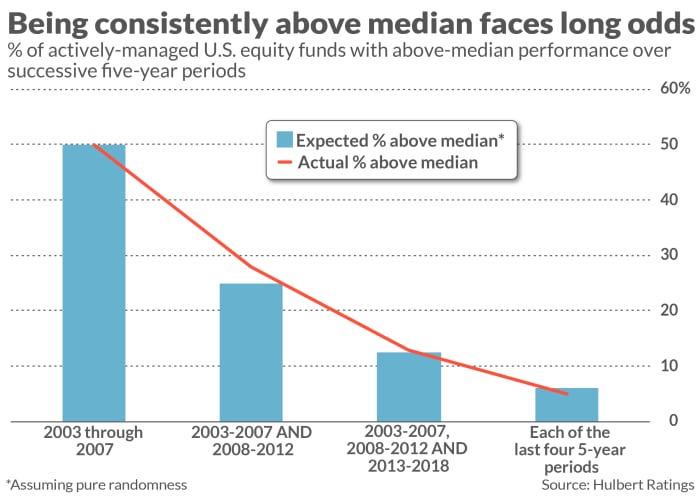

Now consider what happens if you extend this thought experiment to two successive periods. The odds of beating the market in both individual periods fall to 25%. In three successive periods, the odds of being above average are 12.5%, and after four periods the odds are just 6.25%. It’s unlikely that any of a group of monkeys will have beaten the market in four successive periods.

How does the real world compare to this imaginary world of stock-picking monkeys? Pretty close. The odds of success in the mutual-fund world are no better than in this imaginary world — if not worse. Genuine market-beating ability is extremely rare, in other words.

Consider the percentage of actively-managed open-end U.S. equity mutual funds that have been in existence for each calendar year beginning with 2019. In contrast to the 6.3% odds that a randomly chosen fund would be in the top 50% for performance in that year and each of the subsequent three years, the actual proportion was 3.7%. (I conducted my analysis using FactSet data; 2022 returns are through Dec. 9.)

Sobering as these statistics are, they overstate the fund industry’s odds of beating the market in successive periods. That’s because I focused only on those funds that have been around since 2019, and many of the actively-managed U.S. equity funds offered that year have gone out of business. In other words, my results are skewed by survivorship bias.

Is one year enough to judge performance?

One comeback to my analysis is that one year is not a long-enough period over which it’s reasonable to expect a manager to always beat the market. Out-of-left-field developments could cause even the best adviser to lag the market over that short a period, after all — developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, to use two recent examples.

How about a five-year period? When pressed, most investors think that’s a long-enough period over which it’s reasonable to expect a mutual fund manager to be at least above average.

To explore how likely such above-average performance is, I repeated my thought experiment with five-year rather than calendar-year periods. I started by focusing on those funds that were in the top 50% for performance over the five years from January 2003 through December 2007. I then measured how many of them were also in the top 50% in each of the three successive five-year periods — 2008 through 2012, 2013 through 2017, and 2018 until today.

In contrast to the 6.25% that you’d expect assuming pure randomness, the actual percentage was 5.1%. And, once again, this 5.1% overstates the true odds because of survivorship bias.

My thought experiments illustrate how hard it is to find a fund manager that we definitively know to have genuine ability. Because of that, you need to be incredibly demanding and choosy when searching for a mutual fund you will follow. You should resist the temptation to invest in the mutual fund with the best performance over the past year, no matter how tantalizing its returns. Insist that a fund has jumped over enough performance hurdles that there is an extremely low probability that its past performance was due to luck.

I want to acknowledge that the inspiration for the thought experiments I highlighted in this column came from research conducted by S&P Dow Jones Indices called “S&P Indices Versus Active,” otherwise referred to as SPIVA. Though the SPIVA research hasn’t conducted tests that are identical to those I discussed here, they were broadly similar.

S&P Dow Jones Indices is currently celebrating the 20th anniversary of its periodic SPIVA reports. In an interview, Craig Lazzara, Managing Director of Core Product Management at S&P Dow Jones Indices, said that one of the primary takeaways from this long body of research is that “when good performance does occur, it tends not to persist… SPIVA can serve to remind investors that if they choose to hire active managers, the odds are against them.”

The thought experiments I conducted for this column reached the same conclusions.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Americans name their No. 1 financial New Year’s resolution — and the timing couldn’t be better