Congress might only have until this summer to strike a deal to lift or suspend the U.S. government debt ceiling, prompting analysts to warn of growing risks to global financial markets as America moves closer to a potential default.

“It would cause immeasurable harm to financial markets,” Amar Reganti, a fixed-income strategist at Hartford Funds, told MarketWatch. If a debt-ceiling crisis isn’t averted and the government no longer can borrow to cover expenses, he said, “there is no part of modern capital markets that offer shelter” to investors if a substantial U.S. credit rating downgrade occurs.

The U.S. Treasury Department began operating under “extraordinary measures” in January to keep the government current on its bills, after it ran up against its current debt limit of about $31.4 trillion. Since its creation a century ago, the U.S. debt limit has imposed limits on how much the federal government can borrow to meet existing obligations already approved by Congress.

The Congressional Budget Office on Wednesday estimated that the U.S. government could reach its debt limit sometime between July and September.

See: CBO warns of potential for U.S. default between July and September, as debt-limit standoff persists

Reganti at Hartford Funds had a front-row seat to prior U.S. debt standoffs, while serving as the deputy director of the Office of Debt Management at the Treasury Department from 2011 to 2015.

For now, the roughly $24 trillion Treasury market continues to hum along as the world’s deepest and most liquid market. Reganti sees volatility as likely to hit maturing Treasury bills in the coming months, if Congress fails to reach a debt-ceiling deal. But he sees a catastrophe unfolding in markets if the U.S. ends up in default, because its debt has been “hard-wired” into the global financial infrastructure.

For those reasons, financial markets tend to wave off the possibility of a U.S. default as unthinkable, and instead “rely on the fact that historically, while recalcitrant, Congress has raised the debt limit,” Reganti said.

Stock-market fell 15% in 2011 debt-ceiling standoff

Uncertainty typically hasn’t been a friend to financial markets.

Congress already has raised the debt limit 86 times, 18 of which occurred under former President Ronald Reagan, according to a tally from Invesco. The economy back then was reeling from double-digit inflation and the Federal Reserve’s policy interest rate had peaked near 19%.

U.S. inflation looks to have peaked last summer at 9.1%, while the Fed’s policy rate is expected to top 5% in this cycle.

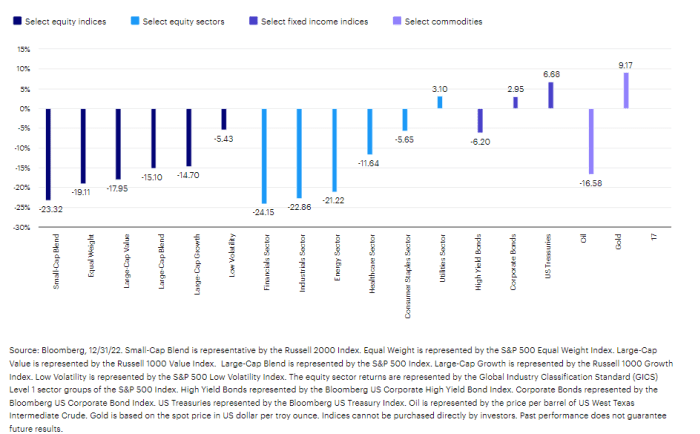

A look at the 2011 debt-ceiling standoff shows riskier assets sold off (see chart), with the S&P 500 index

SPX,

tumbling about 15% from July to September, but gold

GC00,

U.S. Treasurys and highly rated corporate bonds benefited from “safe haven” demand.

Gold and U.S. government debt benefited during 2011 debt ceiling impasse

Bloomberg, Invesco

“What made 2011 so different,” said Brian Levitt, Invesco’s global market strategist, was that Republicans held a significant majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, which allowed them to extract major future spending cuts from the Obama administration in exchange for an increase of the debt limit.

That deal didn’t complete “until the 11th hour,” Levitt said, while adding that a lack of a “red wave” for the Republican Party in the 2022 midterm Congressional elections potentially puts a new debt-ceiling agreement within reach. A debt-limit bill would need 218 votes to pass the House, which is narrowly controlled by Republicans. Democrats now hold 212 seats in the chamber, and would need six Republicans to join them in passing any legislation.

However, if the current stalemate persists, Levitt foresees a similar selloff in stocks from the 2011 period as likely. “It depends on how close to the brink we go.”

Treasury yields, a buffer?

A caveat on the current debt-ceiling standoff is that it’s the first in more than a decade when the higher Treasury yields now prevailing can offer investors a sizable “risk-free” fixed-income return, while also helping cushion their downside risk if stocks sell off sharply.

The 2-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD02Y,

was at 4.66% on Thursday, while the 10-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

was at 3.84%, according to FactSet. That’s up from 1.3% and 2%, respectively, last March.

What’s more, liquidity in the Treasury market has held up during the past three decades of debt-ceiling fights in Congress, according to Shankar Narayanan, head of trading research at Quantitative Brokers.

“The visible liquidity is not affected,” Narayanan said, pointing to historical trading data for Treasury futures and cash markets that signal a past resilience in U.S. government debt.

“It is no different this time,” he said. “But let’s see how that goes heading into the actual event.”

—Additional reporting by Robert Schroeder