U.S. home prices have been rising at a record annual pace in recent months, fueled in part by historically cheap credit, the absence of properties for sale, and the scramble by households for more space as families have fled to the suburbs during the pandemic.

Can the good times last when the Federal Reserve finally cuts back on buying mortgage and Treasury bonds? Here’s how mortgage rates and a less gargantuan central bank footprint could impact the heated U.S. housing market.

“The Fed is certainly talking and thinking about it,” said Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist at the Schwab Center for Financial Research, on the subject of how the Federal Reserve could scale back the central bank’s $120 billion a month bond-buying program.

But Jones also thinks tighter credit conditions, likely via higher borrowing rates as the Fed tapers its bond buying program, might end up being a saving grace for today’s housing market.

“Housing prices could certainly pull back, after accelerating so fast,” she said, pointing to households fighting over the few properties available to buy, while navigating work from home. “At some point,” she said, mortgage payments on high-priced homes “become unsustainable with people’s incomes.”

“But I don’t see a big housing debacle.”

How to pump the brakes on housing

The central bank has maintained a large footprint in the mortgage market for more than a decade, but the worsening affordability crisis in the U.S. housing market led Fed officials to walk a tightrope recently when trying to explain its ongoing large-scale asset purchases during the pandemic recovery.

Fed officials in recent weeks have expressed a fair bit of disagreement around the timing and pace of any scaling back of its large-scale asset purchases.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said Friday the central bank should start to slow down its bond purchases this fall and finish by March, saying he thought financial markets “are very well prepared” for the reduction in purchases.

During a midweek press briefing, Chairman Jerome Powell said tapering likely would start with agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and Treasury bonds at the same time, but also “the idea of reducing” mortgage exposure “at a somewhat faster pace does have some traction with some people”.

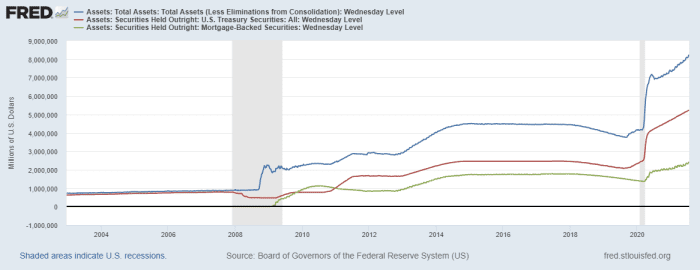

The blue line in the chart below traces the central bank’s balance sheet and abrupt path to a $8.2 trillion balance sheet since 2020 when its efforts to support markets during the pandemic began, with the red line representing its Treasury

TMUBMUSD10Y,

holdings and green line its MBS.

MBB,

Fed holds major cards in MBS and Treasury markets

St. Louis Fed data

As of July 29, the Fed was holding about 31% of the roughly $7.8 trillion agency MBS market, or housing bonds with government backing.

“You could make the case that the Fed owns almost one-third of the agency mortgage bond market, and that it might make sense to loosen its grip,” Jones said, particularly as Powell has played down a direct link between its MBS purchases and climbing home prices.

It may now seem like a distant memory, but before the pandemic upheaval, that was precisely what the Fed was trying to do.

“Who would have thought,” said Paul Jablansky, head of fixed income at Guardian Life Insurance, that the U.S. would be in the midst of “one of the frothiest housing markets in history,” following last year’s extreme pandemic shutdowns that closed businesses, workplaces and national borders.

“Occasionally people ask, are we at the peak?” said Jablansky, a 30-year veteran of the mortgage, and asset-backed and broader bond market. “We are outside the balance of our experience, so it’s very difficult to say we are at the peak,” he told MarketWatch.

“I do think house price inflation will have to slow down dramatically. But maybe the biggest question is, can we see housing prices go negative? I think the Fed will work very, very hard to create a soft landing in house prices.”

Schwab’s forecast has been for the Fed to kick things off by reducing its monthly asset purchases by $15 billion to $105 billion. That would mean cutting $10 billion from its current $80 billion monthly pace of Treasury purchases and $5 billion from its $40 billion monthly pace of MBS.

“So far, we haven’t changed that,” Jones told MarketWatch.

While the Fed doesn’t set long-term interest rates, its mass buying of Treasurys aims to keep a lid on borrowing costs. Treasury yields also inform the interest rate component of 30-year fixed-rate mortgages. So perhaps, scaling back both at once makes sense, Jones said.

Misremembering the 2013 taper

Fed Chair Powell said on Wednesday that the central bank’s “substantial further progress” standard for unemployment and inflation in particular hasn’t been met yet, while stressing that he’d like to see more progress in the jobs market before easing its monetary policy support for the economy.

Powell also frequently has talked of lessons learned from the market upheaval of 2013, the “taper tantrum” that rattled markets after the central bank began talking about taking away the punch bowl, as the economy healed from the Great Recession of 2008.

“What we need to remember,” Jablansky said, is that markets sold off in anticipation of tapering, not the actual pull back in asset purchases. “Later in the year, the period [former Fed Chair Ben] Bernanke was talking about, the Fed actually continued to buy assets, and the amount of accommodation it provided to the economy actually went up.”

Historically, the only stretch where the Fed has actively withdrawn its support occurred between 2017 and 2019, following its controversial, first foray into large-scale asset purchases to unfreeze credit markets post 2008.

“It’s very difficult to draw a lot of conclusions from that real short period,” Jablansky said. “For us, the conclusion is that 2013 may be instructive, but the circumstances are really different.”

The message from Powell consistently has been about preserving “maximum flexibility, but to go very slowly,” said George Catrambone, head of Americas trading at asset manager DWS Group.

Catrambone thinks that may be the right strategy, given the uncertain outlook on inflation, evidenced by, the recent spike in the cost of living, but also because of how significantly many of our lives have changed because of the pandemic.

“We know that a used car won’t cost more than a new car forever,” Catrambone said. “Do I think the housing market slows down? It could. But you really need the supply, demand imbalance to abate. That could take a while.”

Extreme wildfires, drought and other shocks of climate change have been tied to $30 billion in property losses in the first half of 2021, while putting more patches of land and U.S. homes in the path of danger. While these were less frequent housing market topics in 2013, the pandemic also changed the whole notion of “what is safe” for many families.

“Migratory patterns tend to be sticky,” Catrambone said, of the flight out of urban centers to suburbia.

What’s more, the delta variant fueling a new wave of COVID-19 cases has led to stricter masking and vaccination policies, including at Alphabet Inc.,

GOOG,

Facebook Inc.

FB,

and others, but also delayed plans by many big companies to return staff to offices buildings.

“This probably doesn’t help occupancy rates for commercial real estate, with more people likely staying closer to home,” Catrambone said, but it likely adds to the already high “psychological value placed on housing.”

After touching record highs, the S&P 500 index

SPX,

Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

and Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP,

closed Friday and the week lower, but booked monthly gains.

On the U.S. economic data front, August kicks off with manufacturing and construction spending data, followed by motor vehicles sales, ADP employment and jobless claims, but the main focus of the week will be the monthly nonfarm payrolls report on Friday.

Read: Climate risk is hitting home for state and local governments