Some 90 million Americans have low health literacy. They struggle with whether they can have a couple of beers while on medication, for example, and sometimes reach the wrong conclusion.

You may not be one of them, but what if your father is? Or your grandmother? Or the lady who watches over your two-year old?

When you have health literacy, you have enough knowledge about what to do for your health. You also have enough confidence to ask when you’re not sure. And you believe in your own ability to make your health better.

I spent the past two decades studying health and medical choices as a researcher and consulting with the health industry on behavior change. I’ve found there are five proven ways to help a loved one or friend take better control of their health.

1. Translate medical knowledge into very simple terms. Medicine is a world of its own, with a language of its own that only happens to sound like English. People with low health literacy have a harder time understanding it. My research shows that understanding goes with adherence, and adherence goes with better health.

When, for example, you don’t know what atrial fibrillation is (an irregular and often very fast heart rate), you might think it’ll just go away (it won’t) or that you only need to take care of it when you feel its effects (a stroke, which you really don’t want to experience).

If doctors won’t use plain English, intervene. The more you explain the condition and its potential complications in simple terms, the more likely your loved one will understand, take the medication, and in the case of atrial fibrillation avoid getting a stroke.

2. Explain required actions in simple terms. “The big yellow pill” is easier to remember than “Xenosomething.” “Take one after breakfast, and one after dinner” is easier than “twice daily, following meals.” These are subtle but important differences.

Consider downloading an app that sends medication reminders, and shows which medication to take when, and with what, to your loved one’s phone. If they are not at all digital, create a colorful chart with days of the week and times they should take their medicine to ensure they don’t miss a dosage.

3. Ask about what matters. Whenever offered a new treatment, procedure or anything that needs to be considered, ask: What are the risks? What are the benefits? What are the alternatives?

Start with the risks, so you hear about them before you’re lured by the benefits. And I ask about alternatives because you absolutely must know what these are, and the doctor may not volunteer the information unless you probe. Probing is — you guessed it — an important part of health literacy.

4. Don’t assume everyone has confidence. And don’t demand this of anyone. Whenever I take my mother to see a new doctor, she whispers to me, “Tell him you’re a full professor.” Whether I’m a professor or work at juice bar should not matter. But she feels that my profession lands the visit an oomph she otherwise lacks, unfortunately.

Many medical encounters require standing up to a physician, asking for clarification, and demanding alternatives. Be prepared to do this for your loved one when they don’t have the confidence to do it for themselves.

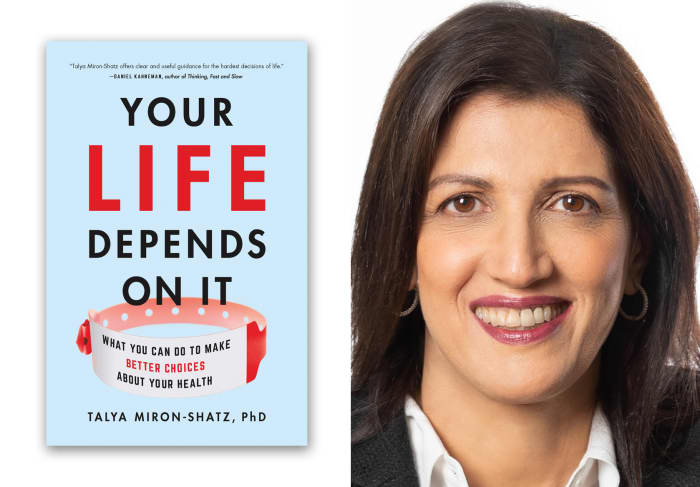

Basic Books

5. Foster motivation. Low health literacy goes hand in hand with a lower belief in your ability to perform the behaviors necessary to attain certain goals. Remember, changing health habits is hard. The first time you go to the gym, all you get are sweat, frustration and sore muscles.

When someone you care lacks the belief in themselves, you can nudge them into doing the right thing (it’s good for them!). Or teach them how to temptation-bundle, as Katy Milkman showed in a recent study: they can treat themselves, during a beneficial but unpleasant activity (for example, listening to an audiobook while on the treadmill). This makes them more likely to do it.

Here’s what it looks like in action. My mom’s doctor told her there was a problem with her bloodwork, something to do with her kidneys and her creatinine levels. She was sitting there, alternating between worry and embarrassment. Was she supposed to know what creatinine is? She had no idea what it was, or how to fix it.

I usually take a back seat when I bring her to the doctor, wishing to respect her autonomy. But health comes before autonomy, so I stepped in and asked, because I did not know what creatinine was either. The doctor explained, in plain English, that my mother was dehydrated. And now that she understood what was wrong, she and her doctor could find a solution.

These simple, powerful, and actionable steps can get those you love to achieve better health. They deserve it, and so do you.

Talya Miron-Shatz is a visiting researcher at Cambridge University, an expert in medical decision making and the author of “Your Life Depends on It: What You Can Do to Make Better Choices About Your Health”. Follow her on Twitter @TalyaMironShatz.

Now read: This is the most important question to ask your doctor to avoid unnecessary medical care

And: Hearing aids could soon cost less than $1,000 and be bought at the drugstore