The U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve is the world’s largest emergency stockpile of crude oil, but talk of a release from the reserve may be only a short-term fix to high prices of oil and gasoline.

“Tapping the SPR will only address the symptoms of what is driving prices higher and cannot solve the tightness in the market,” Matthew Parry, head of long-term analysis at Energy Aspects, told MarketWatch.

During a White House press conference Friday, U.S. Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the U.S. continues to look at “every tool in our arsenal” to lower gasoline prices, and has taken a range of actions, including engaging with entities abroad such as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Releasing more crude from the SPR would have no impact on gasoline supplies, said Anas Alhajji, an independent energy expert, who’s also managing partner at Energy Outlook Advisors LLC.

That option is only one of several that Alhajji has outlined—all of which, he says, are “bad options,” including a ban or limit on crude exports and political pressure on OPEC.

SPR release

The size of any SPR release would matter, said Parry, but what is being considered will likely be only be a “drop in the bucket against a backdrop of very low stocks.”

“The market has already priced in an SPR release to a large extent—and much of the price and spread moves seen in recent days are signs of exactly that,” he said.

Last week, front-month U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude futures

CLZ21,

CL.1,

fell 0.6%, while global benchmark Brent crude

BRNF22,

BRN00,

lost 0.7%.

“Any sell-off related to an SPR announcement will be short lived and will not structurally alter the market,” said Parry. “If anything, an SPR release could bring traders—who have been derisking into year-end due to the uncertainty around the SPR—back to buy crude.”

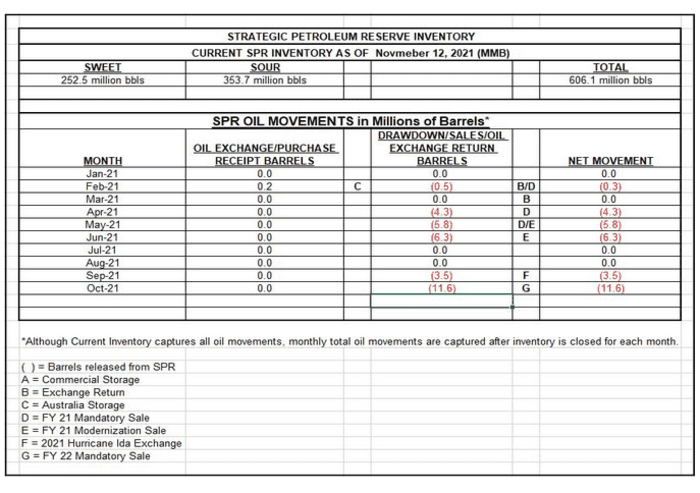

Source: U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management

The SPR was established primarily to “reduce the impact of disruptions in supplies of petroleum products and to carry out obligations of the United States under the international energy program, according to the Energy Department. The stocks in the reserve, which have an authorized capacity of 714 million barrels, are federally owned and are stored in underground salt caverns at four sites along the Gulf of Mexico coastline.

As of Nov. 12, the SPR had a total of 606.1 million barrels of crude oil, following a drawdown of 11.6 million barrels in October, which the Energy Department said was part of a fiscal year 2022 mandatory sale.

One of the more sensible solutions might be to do an “exchange,” Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis at the Oil Price Information Service (OPIS), told MarketWatch.

“Oil could be released in Texas and Louisiana SPR facilities and replaced (by the bidders) some six to 12 months down the line,” he said. “That might ostensibly ease the pressure on winter prices and not compromise emergency reserves down the road.”

To be clear, stocks of the reserve have seen some drawdowns in recent months.

“There have been some recent releases of crude to help counteract the loss of production in the Gulf of Mexico,” said James Williams, energy economist at WTRG Economics. THE SPR saw a drawdown of 3.5 million barrels in stocks in September, citing a “2021 Hurricane Ida Exchange.” But that was “essentially a loan to producer who have restored it,” said Williams.

While an SPR release would “lower crude, and therefore gasoline and diesel prices, it would not solve any problem—and if just for political motives, it would be more effective if done a couple months before next year’s midterm elections,” said Williams.

SPR crude would “mostly go to Gulf coast refiners,” he explained. “They would, in the short term, reduce foreign imports leaving more oil on the international market and lowering prices.”

This, however, “assumes that if we put more oil on the market through the SPR release that it would not impact OPEC output decisions,” Williams said. “If OPEC countered a release by slowing its increase in production quotas, the impact of the SPR could be zero.”

Meanwhile, gasoline prices may continue to be of key concern for consumers.

Regular gasoline prices averaged $3.405 a gallon on Monday, down 2.1 cents from last week, but up $1.285 from a year ago, according to GasBuddy.

“While I think we may have seen the top of gas prices for a few months, I am worried about what we might see next spring,” said OPIS’s Kloza. New refineries worldwide are coming online, but “we’ve lost about 720,000 barrels per day of Gulf Coast refining, PDVSA refining [in Venezuela] is a mess…and we’ll probably see some European closures.”

This could all combine to send certain grades of gasoline, including reformulated gasoline

RBZ21,

$30 to $50 a barrel above crude prices in the second quarter of 2022, “as long as economic growth holds up and COVID doesn’t intervene,” Kloza said.

Pressure on OPEC+

The U.S. has pointed fingers at OPEC as the reason behind the high prices of oil and gasoline.

In an interview with NBC News on “Meet the Press” on Oct. 31, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said gasoline prices are “based upon a global oil market.” The oil market is “controlled by a cartel. That cartel is OPEC.”

Also, earlier this month, President Joe Biden said that gasoline prices are a “consequence of, thus far, the refusal of Russia or the OPEC nations to pump more oil.”

However, OPEC and its allies, including Russia, seemingly ignored pleas by the White House for a bigger production boost and instead, the group known as OPEC+ decided earlier this month to stick to its agreement to lift output gradually, by 400,000 barrels per day in December.

Analysts have questioned OPEC+ ability to meet the production quotas that are already in place.

Only half of the OPEC+ members actually lifted output last month, according to an S&P Global Platts survey released on Nov. 8. The survey said the 19 OPEC+ members with production quotas were a combined 600,000 barrels per day below their allocations in October, according to an S&P Global Platts survey released on Nov. 8.

The survey said the 19 OPEC+ members with production quotas were a combined 600,000 barrels per day below their allocations in October.

Members coming up short of production quotas is a “reminder amid calls for increased OPEC+ output that the group has yet to demonstrate the ability to meet even the current monthly targets,” said Robbie Fraser, global research & analytics manager at Schneider Electric, in a note Monday.

U.S. production and exports

There’s also talk of a U.S. crude exports ban to help lower prices.

A ban on U.S. crude exports “would not be effective, as U.S. refineries can only economically use so much of the light crude that is exported,” said Williams. Many U.S. refineries are “designed for heavier crude,” so a ban on exports would not provide any help.

It’s net imports/exports that matter, and the exports of light crude “help balance the heavy crude imports that are needed,” said WTRG’s Williams.

He thinks the solution to lower prices is to encourage more domestic production.

That could happen “both through leasing more Federal land onshore and offshore and not increasing regulation on the industry, as wells as encouraging, rather than discouraging, lending institutions to support the oil and gas industry,” he said.

“It seems that the policies so far are inconsistent. The actions are that the administration wants more OPEC and even possibly Iranian oil, while at the same time trying to reduce U.S. exploration and production because it causes global warming.”

A global market

The true key in easing the problem of high oil and gasoline prices long-term may go back to what U.S. Energy Secretary Granholm told NBC News back in late October, when she said gasoline prices are based upon a “global oil market.”

Hopefully, the Biden administration will listen to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Agency, and OPEC, which are in agreement that the oil market will tip back into inventory builds in early 2022, “rather than giving into political pressure,” Troy Vincent, market analyst at DTN, told MarketWatch.

“SPR releases are ultimately additional incremental commercial supply and therefore can marginally help ease the current global shortfall in production relative to demand,” he said. But “these releases cannot be the solution to longer term structural shortfalls in investment in oil production, which should be what politicians should be worried about.”

Taking an extreme measure like putting a stop to U.S. crude exports “would only backfire by disincentivizing domestic crude production and thereby exacerbating the issue of high oil prices by guaranteeing the global market remains short supply in the years to come.”

Instead, “everyone must remember the oil market is a global market and prices are set as such,” said Vincent.

“If the Biden administration wanted to truly ease oil supply fears not for just this month, but in the two to three years to come, they could begin to seriously work with Iran and/or Venezuela to bring their oil back to market,” he said. “This would be the most powerful policy response from a price perspective.”