Wall Street has begun to see more borrowers with blemished credit fall months behind on their subprime auto loans, a potential sign of cracks emerging in consumer credit as the Federal Reserve moves to fight inflation.

Subprime auto loans had been a surprisingly strong corner of household debt in the past two years of pandemic, helped by temporary aid from Washington that boosted the finances of many families.

Early indicators now point to a tougher road ahead, particularly for low-wage earners facing higher prices at the grocery store and gas pump, without the child tax credit or other pandemic aid to help.

Read: ‘It’s shameful’: Nearly one-third of U.S. workers make less than $15 an hour

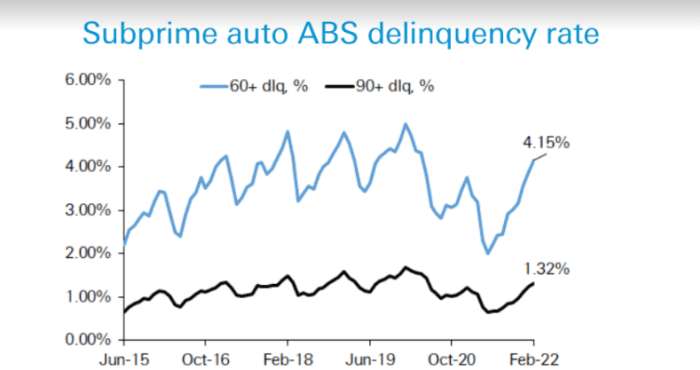

In February, the delinquency rate for subprime auto loans more than 60 days past due rose to 4.15%, the highest since April 2020 (see chart below) for loans packaged into asset-backed bond deals, according to Deutsche Bank.

“We are watching this pretty closely,” said John Kerschner, head of U.S. securitized products at Janus Henderson Investors. “I would say let’s see what happens in the next couple of months.”

Unlike last year, the raft of temporary pandemic assistance for struggling homeowners, renters and borrowers with student debt now has expired or is set to soon end.

“No one was thinking that 2021 was going to be the norm going forward,” Kerschner said, of historically low consumer default rates and high household savings. “Everyone knew it was kind of the best of all worlds.”

The rate of past due subprime auto loans in bond deal reaches 4.15%, the highest since 2020, according to Deutsche Bank.

Deutsche Bank

Fitch Ratings also tracked February subprime auto ABS delinquencies at the highest since April 2020, but at a near 4.8% rate.

While February data is the most recent, Margaret Rowe, senior director in Fitch’s asset-backed securities group, said it’s important to keep in mind that delinquencies for the same category averaged 5.2% in 2019, before the pandemic.

“Certainly, spending power from what we are seeing on inflation could leave the subprime borrower more vulnerable,” Rowe told MarketWatch. “We were expecting to see delinquencies normalize, or come back to those pre-pandemic levels.”

Why credit reports matter

Many investors have been skittish about taking on more risk this year, particularly as more Federal Reserve officials call for an aggressive path higher this year to help cool inflation at 40-year highs.

The S&P 500 index

SPX,

was down 5.5% on the year through Wednesday, while its energy sector was up nearly 40%, according to FactSet, pushed higher by U.S. oil prices

CL00,

above $114 a barrel.

Subprime borrowers often have credit scores in the 619-to-580 range, with those scoring below 580 considered “deep subprime,” according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Subprime auto loan rates can range from about 10% to more than 25%, according to a recent Consumer Reports study, versus below 5% for many prime borrowers.

Auto lenders often move quickly to repossess vehicles when a borrower falls behind on payments. With used car prices up by more than 40% from a year ago, the CFPB recently warned lenders not to jump the gun and illegally repossess cars and trucks.

“Any default is going to impact somebody’s credit significantly,” said Francis Creighton, president of the Consumer Data Industry Association, a trade group representing credit reporting bureaus and agencies.

“If you are subprime, you are digging yourself further into a hole,” Creighton said by phone. He also said that inflation and higher rates mean consumers “are going to be paying more for virtually every kind of credit,” and need to get the best rate possible. “That’s why we tell people to check their credit report.”

Consumers have until April 20 to request free, weekly credit reports from the FTC, as a result of the pandemic. Those reports used to be free only once a year, a help to U.S. households that now owe a record $15.6 trillion in consumer debt, after their balances climbed by about $1 trillion in 2021, the largest yearly jump since 2007.

“We believe inflation is more likely to impact subprime borrowers due to lower incomes and/or savings,” BofA Global’s strategy team wrote, in a weekly note. “This leaves the subprime auto loan ABS and consumer loan ABS sectors more vulnerable to credit deterioration, which could add pressure to ABS valuations in the coming months, especially at the subordinated level.”

But for now, Kershner said a strong job market helps consumers, even as rates are rising and the cost of living is higher. The other thing is that subordinate, or “junior,” subprime auto bonds that would be first in line for losses, aren’t showing significant levels of stress, or spread-widening, that point to credit concerns by investors.

“Everything is widening out, but on a percent basis the top AAA classes are widening out more,” he said. “I’d be more concerned if they were blowing out like in 2020 during the start of COVID.”

Read: Consumer watchdog fires warning shot to lenders over abusive auto repos as used-car prices soar