Should we save a spot in the baseball annals for the “climate-ball” era? Climate change and its impact on home-run-favorable thinner air may earn a place in recorded history alongside Major League Baseball’s dead-ball era and the notorious black eye on America’s pastime when steroids juiced the power game.

The way that climate change heats up the air is sending an extra 50 or so home runs a year over the fences, and fans can expect several hundred more home runs per season with future warming, according to a new study out Friday from Dartmouth College scientists.

They considered a number of characteristics that have changed professional baseball in recent years to favor the long ball, or out-of-the-park home runs, versus so-called small ball, in which even most pros hit for average to get on base, and then move runners into scoring position, sometimes by stealing bases or with a sacrifice hit. We’ve always loved the home run, but power hitters were once rarer and their number of home runs per season — and for many, their strikeout tendencies — fewer.

To be sure, there are several factors at work promoting more home runs, a list not lost on the Dartmouth researchers, themselves baseball fans, who ran the study.

The findings come as no surprise, perhaps, to most fans who can compare the complexion of MLB games in outdoor stadiums in northerly settings early or late in the season to nine innings played on an August afternoon. When air is warmer, it is thinner, and that means less resistance on a ball elevated by a hitter.

But what the study unearthed is how many days each year during the season already are warming up, and how many more will feature warmer temperatures and thinner air in the coming years.

“There’s a very clear physical mechanism at play in which warmer temperatures reduce the density of air,” said senior author Justin Mankin, an assistant professor of geography at the school. “Baseball is a game of ballistics, and a batted ball is going to fly farther on a warm day.”

Opinion: Why baseball’s Opening Day is the real New Year’s Day

Mankin and his team analyzed more than 100,000 major-league games and 220,000 individual hits to correlate the number of home runs with the occurrence of unseasonably warm temperatures. They then estimated the extent to which the reduced air density that results from higher temperatures was the driving force in the number of home runs on a given day compared to other games.

“ Climate change and the way it heats up the air is sending an extra 50 or so home runs a year over the fences, and fans can expect several hundred more home runs per season with future warming. ”

Lead author Christopher Callahan, a doctoral candidate in geography at Dartmouth who conceived of the study, said the researchers accounted for factors such as the use of performance-enhancing drugs; the materials for bats and balls; and the adoption of cameras, launch analytics and other technology intended to optimize a batter’s training to boost power and distance.

Historically, MLB has favored the entertainment value of hitting over, say, a well-pitched low-scoring game. The designated hitter, which most commonly replaces a pitcher at the plate, was adopted by the American League in 1973 and by the National League just last year, making it universal in MLB.

With all this in mind, the researchers made sure to control for such factors.

“We asked whether there are more home runs on unseasonably warm days than on unseasonably cold days during the course of a season,” Callahan said. “We’re able to compare those days with the implicit assumption that the other factors affecting batter performance don’t vary day to day or are affected if a day is unseasonably warm or cold.”

“We don’t think temperature is the dominant factor in the increase in home runs — batters are now primed to hit balls at optimal speeds and angles,” he added. “That said, temperature matters and we’ve identified its effect. While climate change has been a minor influence so far, this influence will substantially increase by the end of the century if we continue to emit greenhouse gases and temperatures rise.”

Is Earth really heating up?

Earth’s temperature has risen by an average of 0.14 degree F (0.08 degree C) per decade since 1880, around the start of the Second Industrial Revolution, when humans readily burned coal, oil

CL00,

and eventually gasoline

RB00,

in vast adoptions that helped more people move out of poverty but began a manmade warming trend that is harming oceans and intensifying deadly heat and natural disasters.

That makes for about a 2-degree F increase in total. The rate of warming since 1981 is more than twice as fast: 0.32 degree F (0.18 degree C) per decade, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Last year was the sixth-warmest year on record, based on NOAA’s temperature data. The 2022 surface temperature was 1.55 degrees F (0.86 degree C) warmer than the 20th-century average of 57.0 degrees F (13.9 degrees C). The 10 warmest years in the historical record have all occurred since 2010, says NOAA. Read more on global temperature changes.

Related: Fighting climate change will take ‘everything, everywhere, all at once,’ say U.N. scientists

Read: Google search adds extreme-heat warnings to its flood and wildfire alerts

So long, outdoor stadiums?

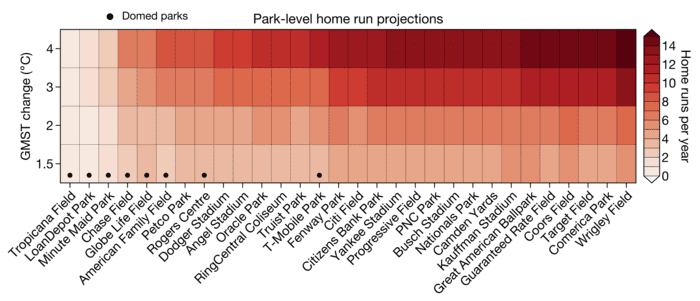

The Dartmouth researchers examined each major-league ballpark for an idea of how the average number of home runs per year could rise with each 1-degree C increase in the global average temperature. Notably, the actual number of runs per season due to temperature could be higher or lower depending on individual game-day conditions.

For instance, the Chicago Cubs’ open-air Wrigley Field would experience the largest spike, with more than 15 home runs per season. That’s in part because the team can host only a limited number of night games due to a city ordinance meant to respect the densely populated neighborhood around the park. Conversely, the Tampa Bay Rays’ domed Tropicana Field would remain level at one home run or less, no matter how hot it gets outside. And the Boston Red Sox’s iconic Fenway Park and the home of their archrivals, the New York Yankees, fall about in the middle of the projections for climate-linked increases. Both would experience nearly the same effect as temperatures rise.

The researchers charted the expected increase in heat-linked home runs based on the current lineup of stadiums.

Christopher Callahan and Justin Mankin/Dartmouth College

Night games would lessen the influence that temperature and air density have on the distance a ball travels, and covered stadiums such as Tropicana Field would nearly eliminate it, the researchers suggest.

Curbing the rise in home runs, and arguably the added excitement they bring to a game, might seem counterproductive. But there are additional factors to consider as global temperatures rise — that is, the dangers of extreme heat and humidity for players and fans, Mankin said.

“A key question for the organization at large is what’s an acceptable level of heat exposure for everybody, and what’s the acceptable cost for maximizing home runs,” Mankin said. “Home runs are one pathway by which temperature is affecting game play, but there are other pathways that are more concerning because they have human risk attached to them.”

Read: MLB umpires will have new view of replays for close calls this season — on Zoom

Don’t miss: Minor league baseball players reach 5-year labor deal with MLB